Wood, paint, silicone, bolts

Wood, paint, silicone, bolts

Wood, paint, silicone, bolts

Painted cast, silicone, oak

Painted cast, silicone, oak

An Intimate Note to Painting, 2022

Painted cast, silicone, nail

An Intimate Note to Painting, (detail) 2022

Painted cast, silicone, nail

19 x 17 x 4 cm

19 x 17 x 4 cm

19 x 17 x 4 cm

Painted cast, varnish

260 x 230 x 45 mm

Painted cast, varnish

26 x 23 x 4.5 cm

Painted cast, varnish

26 x 23 x 4.5 cm

front_web.jpg)

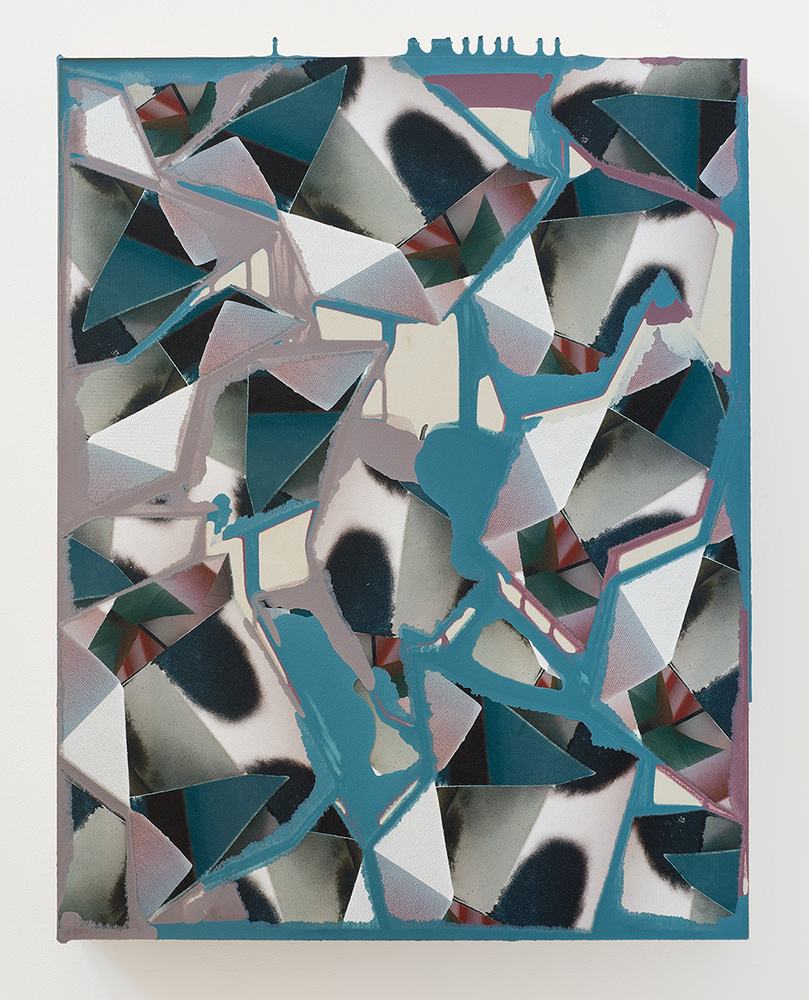

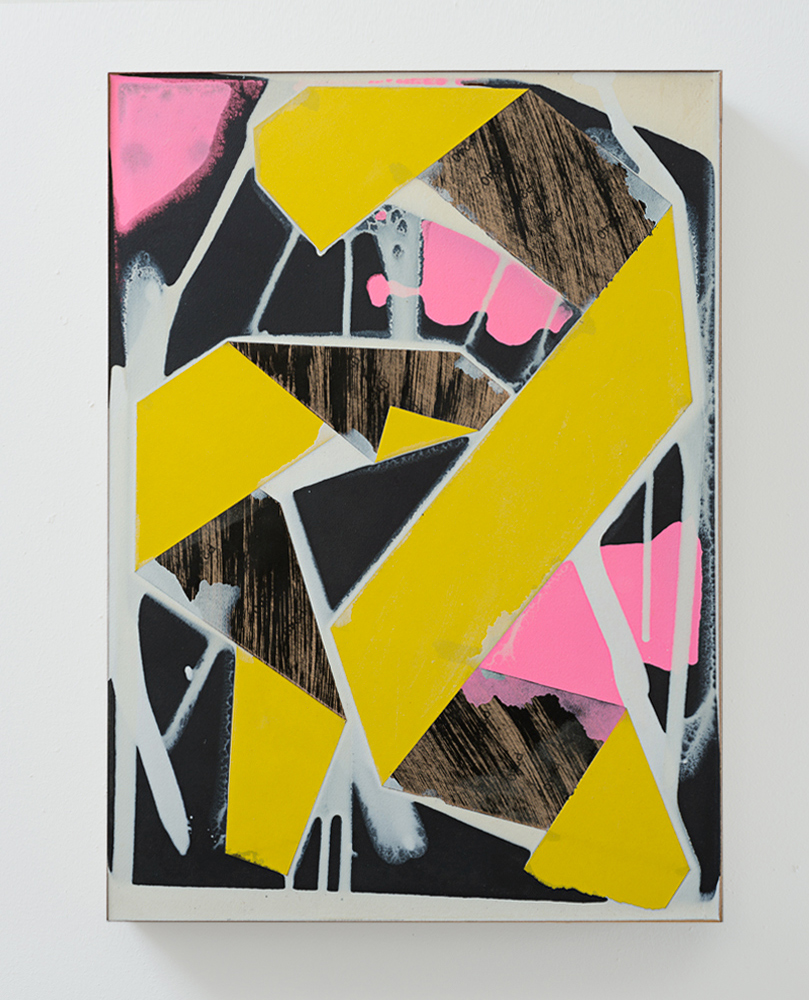

Modelmark series

Resin, enamel

580 x 370 x 110 mm

side_web0.jpg)

Resin, enamel

58 x 37 x 11 cm

bottomedge_web.jpg)

Resin, enamel

58 x 37 x 11 cm

detail_lowerright_web.jpg)

Resin, enamel

58 x 37 x 11 cm

Resin, enamel

23.8 x 16.5 x 6.5 cm

Resin, enamel

23.8 x 16.5 x 6.5 cm

Resin, enamel

23.8 x 16.5 x 6.5 cm

Resin, enamel

23.8 x 16.5 x 6.5 cm

Resin, enamel

16.5 x 13 x 7 cm

Resin, enamel

16.5 x 13 x 7 cm

Resin, enamel

19.5 x 23.5 x 4 cm

Resin, enamel

19.5 x 23.5 x 4 cm

22.2 x 30 x 10.5 cm

22.2 x 30 x 10.5 cm

22.2 x 30 x 10.5 cm

Jim Cheatle is a visual artist and curator living and working in London. Following his initial Painting degree he went on to have a diverse career as a Photographer, Lecturer, Art Therapist and Designer. After studying Communication Design (MA) at Central St Martins he went on to establish his own design practice which he ran successfully for 12 years, before returning back to painting full-time as both curator and artist.

He has been part of a number of critically acclaimed shows in the United Kingdom, both as curator and artist, receiving Arts Council England Funding for his large ambitious group exhibiton at Thames Side Studio Gallery in Greenwich. Showing at the ART021 Shanghai International Contemporary Art Fair and most recently curating and participating with Laure Genillard London, in 'Subradar: The Deceptive Image in the Screen Environment' with the artists Gavin Turk, Andrew Grassie, Susan Collis and Neil Gall. He sells work both internationally and in the UK. He is represented by Star Gallery in Beijing.

Entering Jim Cheatle’s East London studio for the first time, one might easily mistake it for a laboratory of some kind, a workshop belonging to an inventor, an engineer or magician’s cabinet maker. It’s not simply an illusion, either, for the racks, shelves, cupboards and drawers of sometimes familiar, sometimes harder-to-identify objects and materials constitute a trail of evidence leading to Cheatle’s complex, multidimensional abstract paintings. Even his easel seems to take the form of some kind of printing press or machine, a horizontal structure in the middle of the busy room, half obscured by clamps and boards as if to hide the secrets of the work beneath, a handful of clues pinned to the walls.

And the works are secretive in a sense, though cryptic is perhaps a more accurate word, for even the most astute critic or connoisseur would be forgiven for not really understanding exactly what it is that they are looking at when confronted by one of Cheatle’s works for the first time. The surfaces are curious – really curious. There are different textures and materials absorbing or reflecting light to varying degrees, but unlike a conventional handmade (as opposed to digital) collage, the surface seems unified and flat, and the differences in materials are intentionally discreet rather than overt, as if partly submerged within a coherent, overall image. There are just the slightest of ridges where some passages meet others, but even the logic of these does not add up in a way that the eye and mind can easily fathom. In some instances, at a seam where one might reasonably expect a ridge to be, there is none. And vice versa. It is virtually impossible to decipher what might be overlapping what, why colours bleed in some places but not others, and how some sections appear to actively interact or enter into physical dialogues at the expense of others. The surface is a mystery, an enigma. It is like a cryptic crossword, requiring detective work to try to piece together how each work has been created and to comprehend how it functions as both an image and a painting.

The mechanics of precisely how Cheatle has managed to create a painterly collage of eclectic materials embedded within a unified, flat surface are worthy of a text in their own right (and it’s conceivable that his method is a genuine innovation in art), but suffice it to say that Cheatle’s process is a complicated one involving moulds, wooden blocks, resin and pigments, not to mention using his studio in gymnastic ways. Behind the surface of each work, within quite a deep armature, is a surprising, almost sculptural three-dimensional rig, like backstage at a theatre, with lots of activity going on out of sight in the service of the performance out front. But it is the resulting visual language, the ensuing semiotics and aesthetics of the surfaces of the works that clamour for the viewer’s attention, for they are as critically ingenious as the means by which they are created.

There is a polyphony of mark-making within each work and across the whole series, ranging from inks pooling and diffusing freely to bold, graphic geometric shapes that are almost, but not quite fully opaque; there are smudges and smears, scratches, drips, washes and imprints, shadows and reflections. But what’s unusual is that there are passages that look like these marks and qualities but are actually images of them. For some passages are self-consciously blurred, or have another light source internal to themselves that makes clear that photographic and print processes have also been involved somewhere down the line. As if it wasn’t already complicated enough to decipher and to describe, Cheatle has literally added a whole other dimension to the work by photographing abstract sections of his works, printing them and then incorporating these reproductions in subsequent works, like wormholes in time and space, or simulacra hiding in plain sight amidst originals. Indeed, the works are highly self-reflexive, generating content from within themselves for the next work, like some strange, organic abstract reproductive system.

The upshot is that there are sections that are flat and actual size, sections that are close-ups where we zoom in on a material or vignette, and other passages where we are looking at three-dimensional forms from an oblique angle with no sense of scale to guide us. It is even difficult to ascertain what kind of materials we are looking at in many cases – while there are sections that look distinctly like MDF, paper or canvas, there are others that slip beyond definition, into pure colour or unidentifiable texture – some matte, some gloss, others seemingly embossed. The eye and the mind can easily become overwhelmed when trying to come to terms with the myriad modalities that Cheatle has created within his picture plane, like an abstract hall of mirrors.

This latest body of work, which continues Cheatle’s long-standing interest in mark-making, processes of reproduction and simulation, and the interface between the real and the digital, makes a provocative and stimulating contribution to the practice and discourse of abstraction today. It is thoroughly postmodern (in a good way), and is completely disorienting (again, in a good way). Cheatle takes the ground from beneath the viewer’s feet, destabilising our traditional categories of medium and iconography (I’d love to know what Panofsky would have made of these works), and creates something that one would normally imagine only to be possible digitally, here presented live and direct as a ‘real’, tactile, physical object – it might, on-screen or on first glance, look like a Photoshop collage, but it is a real painting, running rife with materials and processes. In an era of image overload, our usual speedy perception and cognition are forced to stop in their tracks and made to work that bit harder to get to the bottom of all this. Visual modes and materials are fused seamlessly, artifice and artefact united in a harmonious riot of shards of colour, pattern, shape, image and texture, all cleverly – and quite beautifully – orchestrated by the artist without even letting on if a brush has actually been used (or harmed) during the making of any of the works. They are paintings without a painter, abstract works made up of other abstractions in an ongoing, partly selfgenerating feedback loop. With this body of work Cheatle has succeeded in making abstract paintings that are highly relevant in a digital world.

UPDATES IN PROGRESS

Thames-Side Studios Gallery

Jim Cheatle, Alison Goodyear, Alexis Harding, Peter Lamb, Antoine Langenieux-Villard, Donal Moloney, Sarah Kate Wilson.

Curated by Jim Cheatle

Preview: Friday 18 May 2018, 6.30-8.30pm

Download the Surfaced exhibition catalogue

SURFACED: SURFACE AND MATERIALITY IN THE SCREEN ENVIRONMENT

During the 90’s when discourses regarding the position of painting in relation to the screen and ‘new media’ were prevalent, the pixel – perhaps a specificity marker of this new medium was still apparent. The desktop computer had already become a powerful simulator, offering immersive experience with infinite layers and real world metaphors that we were able to grasp onto; files, folders, paths, etc.

However it had not yet become the seamless omnipresent virtual environment that we know today. Social media had barely begun and as late as 1998 only 9% of UK national households had internet access (1). Today in 2017 more than 90% have access. The frequency of internet use has grown from 35% of 16.2 million adults using it daily in 2006, to 80% of 40.9 million in 2017(1). In 2016 it was reported that the average American devotes more than 10 hours a day to a screen of one type or another. (2)

The pixels have long since diminished in size and are no longer discernible as displays on both desktops, mobiles and handheld devices increasingly offer higher definition, while processing power has increased exponentially to supply them. The screen has become an ever-present material condition of viewing and increasingly this luminous environment provides many with their first encounters with works of art.

Our relationship with the screen and the interface isn’t simply a visual one, it has changed from being a tool that we used at our leisure, to a necessary conduit for social interaction, pavlovian in its schema and invisible in its ubiquity, the screen is the threshold of our dematerialized condition. Painting takes its place in the world alongside and within this dominant way of seeing, reconfiguring our relationship and understanding of what is ‘real’ and tactile.

REAL PAINTING

Does this environment create an underlying pressure for artists to make work that is more screenable, quicker to apprehend, less concerned with scale and depth? Or, does it reinvigorate the ‘real’ and the haptic? Can we view work with the same engagement as before, can we still ‘look’ at it in the same way?

Writer and publisher Matt Price describes a recent series of paintings by Jim Cheatle;

“[He] creates something that one would normally imagine only to be possible digitally, here presented live and direct as a ‘real’, tactile, physical object – it might, on-screen or on first glance, look like a Photoshop collage, but it is a real painting, running rife with materials and processes. In an era of image overload, our usual speedy perception and cognition are forced to stop in their tracks and made to work that bit harder to get to the bottom of all this.” (3) Matt Price, 2016

Prior to digital media these differentiations wouldn’t have been needed, and perhaps the work might have been described more historically and in relation to other works of the time. Are we ‘forced’ to stop and work harder? What happens when we are compelled to assert the materiality of work because it’s viewed on the screen?

Perhaps analogous to this is the experience of exiting the cinema, there is sometimes a lingering sense that the world outside has been tinged or abstracted from how it was before entering. Almost as if the cinematic experience has bled over into reality, and for a while this can be felt, until it fades like an afterimage. If we were continuously exposed to film in this way, would this experiential afterimage persist and would we be able to discern

its effect?

“One thing about which fish know exactly nothing is water, since they have no anti-environment which would enable them to perceive the element they live in.” (4)

Marshall McLuhan, 1968

When we engage with works of art now, when we consider the meaning of surface and materiality, is it possible that an experiencial afterimage from our daily interaction with screens is still present?

MATERIAL RELATIONS

Giulliano Bruno, author of ‘Surface: Matters of Aesthetics, Materiality and Media’6 proposes that materiality isn’t necessarily a question of materials but rather concerns the substance of material relations, that theoretically materiality can be thought of as a surface condition. She opens her book with the following quote from the Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius:

There exists what we call images of things

Which as it were peeled off from the surfaces

Of objects, fly this way and that through the air...

I say therefore that likenesses or thin shapes

Are sent out from the surfaces of things

Which we must call as it were their films or bark.(6)

Titus Lucretius Carus, c. 99 BC–55 BC

Bruno argues that the surface of the screens surrounding us today express a new materiality as they “convey the virtual transformation of our material relations”. In her online article ‘Surface Encounters’ 2015, (7) Bruno points out that the haptic is what makes us “able to come into contact with” things, thus constituting the reciprocal contact between us and our surroundings, however hapticity is also related to our sense of mental motion, as well as to kinesthesis - the ability of our bodies to sense the mutable existence of things and movement in space.

“...these screens, which have become membranes of contact, exist in our environments in close relation to the surfaces of canvas and walls—also undergoing a process of substantial transformation. And so it is here—in this meeting place that is surface—that art forms are becoming reconnected and creating new, hybrid forms of admixture.” (7)

Giulliano Bruno, 2015

1. Office For National Statistics: Internet Access - Households And Individuals, 2017: Published 3 August 2017

2. Nielsen Company Audience Report: http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/reports/2016/the-total-audience-report-q1-2016.html

3. http://www.fusedmagazine.co.uk/jim-cheatle-fragmentation-series/

4. Marshall McLuhan, War and Peace in the Global Village, Bantam, NY; reissued by Gingko Press, 2001 ISBN 1-58423-074-6

5. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book XI: The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis (ed. Jacques-Alain Miller), N.Y.: Norton, 1998

6. Surface: Matters of Aesthetics, Materiality, and Media, Giulliano Bruno, University of Chicago Press; 2014

7. Surface Encounters: https://remaimodern.org/pre-launch-programs/supercommunity/surface-encounters-giuliana-bruno. 2015

........................................................................................................................

Summer Salon at Luborimov / Angus Hughes Gallery

JOHN BUNKER: TAINTED LOVE: THOUGHTS ON ‘SURFACED: SURFACE AND MATERIALITY IN IN THE SCREEN ENVIRONMENT’

Antoine Langenieux-Villard, Donal Moloney, Sarah Kate Wilson.

1. Tainted Love…

It is taken for granted in the realms of popular music that the qualities of the human voice, whether vulnerable and haunted or ecstatic and soulful, can be commingled with the repetitions and sequencings of both electronic and sampled sound. Think of Donna Summer’s 70s hedonistic anthem I feel Love, Soft Cell’s magisterial rendition of soul classic Tainted Love, Grandmaster Flash’s White Lines, Prodigy’s Firestarter or Underworld’s Born Slippy. The list goes on and on.

This particular form of genre-breaking music history has relevance here, because I think it has some kind of connection with Surfaced, an exhibition of paintings in Woolwich Arsenal, east London. We are now fully engaged with the delirious levels of innovation and possibility that are opening up in this digital age. Surfaced asks: how might painting be seen differently as an art form in relation to this technological revolution? Just as the human voice has found new and meaningful relationships with electronically generated sound, how will painting deal with the digitised visual world channeled to us by screens?

2. Don’t touch me, please! I cannot stand the way you tease!

We are, by turns, either frightened or aroused by the power of the all-pervasive screen, with its seemingly infinite potential for communication, and for the mining of visual information. It threatens to control us, but at the same time it offers us some notion of creative liberation. This idea of liberation, both personal and political, has also been a subtext of modernist art, and especially of abstract art, since their brutal beginnings in the ferment of industrial and political revolution, and of two world wars: and it is made manifest in the countless nuances and energies, both visual and physical, that define painting’s potential for mediating human experience. There is an irony, then, beneath the surface of Surfaced: that by working to make us aware of how our vision has been lit up in new ways by the ubiquitous screen, the exhibition nevertheless brings us face-to-face once more with painting’s haptic materiality, its singular agency, its ‘hereness’ and ‘thereness’.

3. You think love is to pray, but I’m sorry, I don’t pray that way…

Of course, it is widely believed that abstract painting has relinquished its position as the standard bearer of all that is most advanced in art. The story goes like this: the hollowing-out of its expressive potential began with the ironies of Johns and Pop-era Warhol, and entered its terminal phase with the nihilistic procedures of ‘Neo-geo’ artists such as Peter Halley and Ashley Bickerton. Now, in its ‘post-historical’ condition, abstract painting cannot express any sense of a new social reality, or so the argument runs; and it should therefore mind its own business, exploring its own history of forms, and ruminating upon its own peculiarities and qualities. This reading entirely fails to recognize the degree to which the will to create self-sufficient abstract images clashes headlong with the changing social, political and technological realities of the present day, and, in doing so, acts as the agent of change that generates real innovation in painting. The warping of the picture plane by anterior forces haunts the history of abstraction; there has got to be some kind of fly in the ointment, or grit in the pigment, to create friction, and thereby generate the heat that will be the catalyst for change. The work of each of the artists in Surfaced seems to be alive, in different ways, to this kind of frisson or tension.

4. Sometimes I feel I’ve got to run away…

Alexis Harding’s sumptuous surfaces are formed by the slippage of paint layers as they succumb to the force of gravity. A new kind of expressivity asserts itself, born of a series of booby-traps set by the differing drying speeds of the varied paints he deploys. This process-driven approach works to undo the initial formal ordering or structuring of the painting surface: allowing free rein to the innate entropic qualities of the paint hastens the disintegration of formal order (in Harding’s case, usually a grid-like structure). In Landing (twice) (2018), we see just how sensitive he is to complex densities of colour that pack a real punch. Meanwhile, his fellow John Moore’s prize winner (1), Donal Moloney, offers us a different kind of ambitious painterly complexity: in his one exhibited watercolour on paper, a myriad of shards and splinters of imagery are buried and fused, jewel-like, in the painting’s rippling facets and surfaces. One is reminded of the atomising dabs of colour in Monet at his most experimental; the late modernist all-overness of Larry Poons; even something of the kaleidoscopic and metamorphic writhing imagery of Hieronymus Bosch.

5. The love we share, seems to go nowhere…

The criticism often aimed at mixed-media art is that, for all its conglomerations of different stuff, the results remain dull, lacking the movement and luminosity of unsullied pigment against canvas. Surfaced seeks to address this argument by presenting works that juxtapose meldings of ethereal imagery and finely-judged colour with punchy and immanent materiality. Sarah Kate Wilson’s Shrink Wrap paintings, in their brutal immediacy, work as a corrective to notions of slick, digitised finish. These works contain an array of materials, objects and images that in some cases have been collected by people who have then been invited by the artist to add these material gifts to the shrinkwrapping process. These arbitrary mixtures of objects and images are then flattened within layers of plastic film, pulled over stretcher frames, and left tightly bound in a sort of glistening lo-fi suspended animation. They court the languages of the Support/Surface group of late 60’s Europe; but they also meld these high art associations with the startling arbitrariness and often brutal absurdities to be found on an everyday search of the internet.

Indeed, echoes of Support/Surface can be heard throughout the show. Jim Cheatle and Antoine Langenieux-Villard both foreground how the structure of the support can create its own visual language as it simultaneously underpins and undermines the picture surface. Cheatle brings the folded planes of a cubist vocubulary to bear on painterly bleeds of colour. This pushing of hard edges against soft gradients generates illusions of shallow space, creating a peculiar rhythmic visual charge. In a free-standing work angled across the centre of the gallery, Langenieux-Villard creates calmer rhythmic turns, rendered in repeated gestures of cooler tones. The gentle, meandering gestural marks move in shifting blue tones across some sort of transparent surface, anchored in a deep box frame: the subtle tonal transitions encourage careful looking as one moves around the boxed images. As one peers through its translucent surfaces, moments from the quiet street outside the gallery are captured and held within it: framed by the cabinet-like form, they float in and out of focus.

6. Once I ran to you, now I run from you…

It is in the work of Peter Lamb and Alison Goodyear that the two realms- digitally reproduced imagery and painterly concerns- are most overtly combined. The results are by turns subtle, mesmerising and unsettling. Goodyear’s paintings seem to open up a world of endlessly shifting planes that banish all hope of finding grounding horizon lines or hard edges that might anchor our gaze with easy compositional devices. Like Moloney, Goodyear and Lamb present vaguely familiar signs from the history of modernist abstract painting that simultaneously suggest both dense all-overness and rampant materiality. We soon realize, however, that this overt painterliness is being allowed to evaporate into seductive representations of itself. Goodyear conjures a sense of other worlds- almost submarine or jungle-like; beautiful orchestrations of tonal colour, pale and wistful, create subtle optical play-offs between translucency and opacity. We are momentarily permitted to glimpse submerged worlds within the paintings: much as one would peer into a deep woodland stream.

By contrast Lamb, with an audacious use of size and oscillating scale, ushers us into a mesmerising but disorienting painterly hall of mirrors. Suggestive imagery, based on photographs of lobes and conglomerations of drying paint, sends the eyes skating back and forth across the image surfaces, vainly seeking some sort of equilibrium. The physical reality of aluminium frames within frames is played off against representations of window-like structures and arcs which, in turn, evoke the open ‘windows’ of Photoshop, or other such software, laying open in layers on a computer screen. Lamb also allows unstretched man-made material, with imagery imprinted deep within it, to hang listlessly away from the paintings’ synthetic surface. In contrast with Alexis Harding’s evocations of entropic, geological time, Lamb summons up the sense of mere nanoseconds of perception as the eye flits between the micro and the macro. Underneath all this there lies a suggestion of the highly stylised fashion and art photography of the postmodern era; but Lamb also seems fascinated by the opulent and sumptuous surfaces of late-modernist painterly painting (think Poons again, and also Bowling and Olitski).

He seems to digitally twist and turn this dense painterly matter over and over, adding layer upon layer of imagery as he goes; and one is also reminded of the giant mega-tarpaulins, that new generation of hoardings that can cover the entire sides of multi-storey buildings in advertising imagery. In all of this, there is a strong sense of visual hide-and-seek: the obsessional layering of films of paint of many a late modernist painter finds its equivalent in Lamb’s endless overlaying of representations of painterly imagery, which seem to bleed back into one another, or suddenly split apart, only to reconfigure via the operations of the computer screen. And yet, despite all these digital manouevres, the level of complexity in colour-play and the just-so melding of contrasting formal arrangements, born of inherently visual decision-making, makes this painting with a capital ‘P’. The overall effect is scintillating and fascinating. Each painting has a singular presence and a weight all its own.

7. Touch me, baby, tainted love….

Historically, in its attempts (and frequent failures) to deal with the ravages and revelations unleashed by modernity, abstraction has strayed into unfamiliar territories. In doing so, it has found itself engaging in dialogues with other media: and yet it has been argued these other media- photography and film in particular- are far better suited to expressing the spirit of an age than painting. Surfaced advances a counterargument: that abstract art is able to absorb and ingest aspects of other media, and in so doing, offer a critique of those media whilst continuing to reinvent itself. This is the impetus that will carry abstract painting, in its expanded forms, into the future. It is the wonders, the cruelties, the ironies and social peculiarities of our age- and of the new media in which they are expressed- that have poisoned, and will continue to poison, abstract painting. And it’s the taste of that poison that keeps us coming back for more.

I love you though you hurt me so, I’m gonna pack my things and go.

Link to original John Bunker essay here

Download a PDF